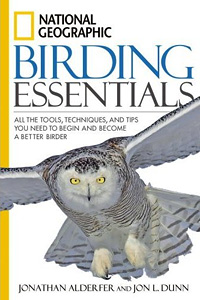

By the third page of text, National Geographic's new book "Birding Essentials: All the tools, techniques, and tips you need to begin and become a better birder" (Jonathan Alderfer / Jon L. Dunn) states:

"Putting a name to a bird is the first step in preserving and protecting it. Without names, birds are generic and often ignored, but once you attach a name to a species, both it and you are transformed. For then you can consider this particular bird's nesting requirements, its feeding niche, its migratory pathways, and its singularity; and you care about its welfare. Because of our connection with birds, it's natural for many of us to become active conservationists. As a birder, your grassroots awareness of the local environment will place you among those best informed about conservation issues in your community whatever your political affiliation."

What a refreshing way to introduce birding to beginners. I've heard it said that the least important piece of information about a bird is the name we've given it – mere language tokens used to announce or note the presence of particular species. But how quickly a set of these names can become documentation used to help measure the quality of an otherwise ordinary looking tract of habitat. Glancing over a field along a country road and associating it observationally with Henslow's Sparrows, Bell's Vireo, Upland Sandpipers, Western Meadowlarks and Bobolinks advances our appreciation of the land.

Though this wasn't always apparent to me when I was a new birder, over time I learned that native grasslands are one of the fastest shrinking habitats in the United States, and thus, so are the numbers of their feathered inhabitants. From coastal shores, wetlands to boreal forests, habitats can be placed contextually with lists of birds associating in them. Experienced birders not only link birds with habitat, but also habitat type with very specific birds – they identify land patterns and can often predict which bird species might be utilizing it at different times of the year.

Though I've not yet read it from cover to cover, Birding Essentials will probably become the "intro-to-birding" book I point to people who are interested in honing their bird identification skills and fieldcraft. The guide is rich in information, beautifully illustrated with color photographs, charts, and diagrams, covering nine comprehensive subjects:

- The Pleasure of Birding

- Getting Started

- Status and Distribution

- Parts of a Bird

- Variation in Birds

- Identification Challenges

- Fieldcraft

- Taxonomy and Nomenclature