Thursday, November 30, 2006

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

The Bird Must Die!

Have you ever noticed the pessimism some birders express when it comes to the survivability of vagrant or late birds, especially during late fall or winter? There's even almost a prideful sense of knowledge embraced being the bearer of bad news that the bird will probably die. There's a cold front coming in tonight and the Wisconsin Bird Network is abuzz concerning a hummingbird in Kenosha. Invariably, along comes the sentiment that if the bird doesn't leave soon, it will most likely succumb to the cold and perish.

Well...perhaps, but not so fast.

What's wrong with being optimistic about its chances? I am. Of course I know the hardships of migration will eliminate millions of birds each spring and fall, but I think many such vagrants, especially hummingbirds, are heartier and more resilient than we've understood in the past and presently give them credit for. Why is it assumed that the vagrant bird we're watching is the one that's going to die?

I'll not deny that vagrancy can be costly. If studies on mortality rates and vagrancy exist, I would be very interested in learning about them. However, I do know there are records of late vagrant hummingbirds banded in the northeast, recaptured only days later further to the south after a major cold front had moved through. Amazingly, in other cases banded birds were recaptured in subsequent years having endured the "vagrant path" more than once.

What are these birds truly capable of? Take the Ruby-throated Hummingbird and its migration potential. It can cross the Gulf of Mexico in a non-stop 24-hour flight. That's around 600 miles! When survival is at stake, how much distance can other hummingbird species put between them and a storm front? Give them a little credit!

Hummingbirds can also thermoregulate their body temperature to drop almost 50 degrees and go into torpor - a type of nocturnal hibernation or noctivation. Their heartbeat can decrease from 500 beats per minute down to 50, lowering its metabolic rate by as much as 95%. Even its breathing may briefly stop.

Some have said torpid hummingbirds exhibit a slumber that is nearly as deep as death. In 1832, Alexander Wilson first described hummingbird torpor in his book, American Ornithology; "No motion of the lungs could be perceived ... the eyes were shut, and, when touched by the finger, [the bird] gave no signs of life or motion."

Nevertheless, they awake. It takes a hummingbird nearly 20 minutes to come out of torpor and a bird in such a lethargic state is very susceptible to being taken by predators. But that's the give and take of such a survival strategy - good for enduring cold snaps, but potentially dangerous in other ways. That it is an adaptation is a powerful indicator that it works far more often than it fails.

Anyway, I observe this gloomy "bird must die" sentiment over and over again. The lingering Cave Swallows that came through the Midwest last winter all died. The Ash-throated Flycatcher that was seen up until a severe cold snap died. Some birders confessed to me that they thought the Yellow-rumped Warbler in my backyard last year would die the night the temperature dipped to 15 below. Well, it didn't. But they killed it off when another birder told me that a Cooper's Hawk must have eaten it after the warbler hadn't been see for a few days.

Just because such a bird is no longer being seen doesn't necessarily mean it died. Of course it doesn't prove it survived either. Where's the corpse? But if vagrancy means certain death, as some birders on listservs invariably portray it, then why does it exist? I mean, can't a bird just fly away every once in a while?

All images © 2006 Michael McDowell

Well...perhaps, but not so fast.

What's wrong with being optimistic about its chances? I am. Of course I know the hardships of migration will eliminate millions of birds each spring and fall, but I think many such vagrants, especially hummingbirds, are heartier and more resilient than we've understood in the past and presently give them credit for. Why is it assumed that the vagrant bird we're watching is the one that's going to die?

I'll not deny that vagrancy can be costly. If studies on mortality rates and vagrancy exist, I would be very interested in learning about them. However, I do know there are records of late vagrant hummingbirds banded in the northeast, recaptured only days later further to the south after a major cold front had moved through. Amazingly, in other cases banded birds were recaptured in subsequent years having endured the "vagrant path" more than once.

What are these birds truly capable of? Take the Ruby-throated Hummingbird and its migration potential. It can cross the Gulf of Mexico in a non-stop 24-hour flight. That's around 600 miles! When survival is at stake, how much distance can other hummingbird species put between them and a storm front? Give them a little credit!

Hummingbirds can also thermoregulate their body temperature to drop almost 50 degrees and go into torpor - a type of nocturnal hibernation or noctivation. Their heartbeat can decrease from 500 beats per minute down to 50, lowering its metabolic rate by as much as 95%. Even its breathing may briefly stop.

Some have said torpid hummingbirds exhibit a slumber that is nearly as deep as death. In 1832, Alexander Wilson first described hummingbird torpor in his book, American Ornithology; "No motion of the lungs could be perceived ... the eyes were shut, and, when touched by the finger, [the bird] gave no signs of life or motion."

Nevertheless, they awake. It takes a hummingbird nearly 20 minutes to come out of torpor and a bird in such a lethargic state is very susceptible to being taken by predators. But that's the give and take of such a survival strategy - good for enduring cold snaps, but potentially dangerous in other ways. That it is an adaptation is a powerful indicator that it works far more often than it fails.

Anyway, I observe this gloomy "bird must die" sentiment over and over again. The lingering Cave Swallows that came through the Midwest last winter all died. The Ash-throated Flycatcher that was seen up until a severe cold snap died. Some birders confessed to me that they thought the Yellow-rumped Warbler in my backyard last year would die the night the temperature dipped to 15 below. Well, it didn't. But they killed it off when another birder told me that a Cooper's Hawk must have eaten it after the warbler hadn't been see for a few days.

Just because such a bird is no longer being seen doesn't necessarily mean it died. Of course it doesn't prove it survived either. Where's the corpse? But if vagrancy means certain death, as some birders on listservs invariably portray it, then why does it exist? I mean, can't a bird just fly away every once in a while?

All images © 2006 Michael McDowell

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Monday, November 27, 2006

World's Deepest Swimming Pool

Vortex Viper - Binocular Review

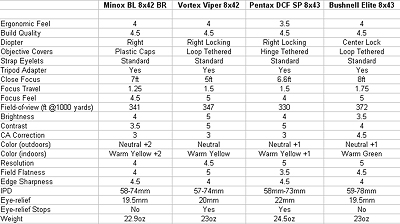

Recently, I conducted a side-by-side binocular comparison with the Vortex Viper against similarly featured models at various price points, all under $1,000.00. When conducting binocular tests, I don't like to include too many binoculars, so you may opine that some obvious favorites are missing from this review.

Though the Viper is available in three magnifications (8x42, 10x42 and 12x42), I compared only 8x models. All binoculars were tripod mounted against standard resolution charts at 50 feet with indoor lighting. I also brought the binoculars outside for distance, color and brightness tests at different times (including dusk) on an overcast day with good atmospheric conditions.

Binoculars used for this comparison/review:

My Score Card:

(click on image for larger version)

Ranking: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = above average, 5 = outstanding.

Ergonomics / Build Quality

All four binoculars felt very comfortable in my hands leaving only minor points to be critical over. The Pentax is slightly bulkier than the other three binoculars. All four are waterproof and nitrogen purged – build quality seems very high and suspect all would be dependable in the field. If pressed to rule one out on perceived build quality, the Minox would be the last of the four I would pick if going on a mountain hike or birding in a damp rainforest.

The Pentax and Viper both have a right-side locking diopter, while the Elite has a center diopter beneath the focus knob that locks. The Minox has a standard right side non-locking diopter ring. The Pentax has tethered objective lens covers attached at the hinge (I don't like those), but that's still better than the separate plastic covers that are easily lost (what the Minox comes with). The Elite and the Viper have looped tethered objective lens covers (my favorite) that are easy to cover and uncover. Each binocular has standard strap eyelets and are also threaded on the central hinge to connect to a standard binocular tripod adapter.

Focus Wheel / Travel

In testing the focus wheels I looked for comfort, focus travel/speed and smoothness. All four binoculars are between 1.25 and 1.75 turns from close-focus to infinity Minox: 1.25; Viper: 1.5; Pentax: 1.5; Elite: 1.75. All were similar in smoothness when turning the focus knob – none were stiff or had noticable play. The Viper and Elite were smoothest and the Pentax seemed to have only slightly more resistance.

Close Focus and Field of View

A super-close focus isn't critical for my applications, so even the Elite with an 8 foot close focus is satisfactory. The Pentax was 6.6 feet and the Minox has a 7 foot close focus. The Viper came in with the best close focus at 5 feet. At 347 feet @ 1,000 yards, the Viper's field of view is generous for its price range and beat the Pentax and the Minox. Naturally, the more expensive Elite topped out in this category with 372 feet @ 1,000 yards.

Brightness, Contrast and Color

The Viper was the clear winner on brightness – a discernible difference over the other three. The Pentax and Minox seemed about the same to my eye. The low mark for the Elite doesn't necessarily mean it's a poor low-light performer, it's just not quite as good as the others in the tests I conducted. I could not detect any negligible difference in contrast between the Pentax and the Viper. The Elite was a close runner-up with the Minox being about average.

The Bushnell Elite topped the other three in correcting chromatic aberration (purple/green color fringing) and I was unable to detect any significant difference between the other three binoculars. In outdoor lighting, whites seemed a little warm on the Pentax and Elite, but the Minox was the warmest. The Viper was the most color-neutral and pleasing to my eye of the four. In indoor lighting, as expected, all of the binoculars appeared to be a little warm but the Elite had more of a greenish tinge when looking at whites. The Minox remained the warmest of the four in indoor and outdoor lighting.

The Pentax and Elite were about even for resolution and ranked highest in my evaluation, but the Viper had a clear advantage over the other binoculars for field flatness. By field flatness, I mean the tendency of vertical objects (like a telephone pole) to remain a straight line when bringing it to the edge of the field. To be fair, the Elite has a larger field of view and I ranked it nearly as high as the Viper. The Pentax had noticeable field curvature among the four binoculars. I was unable to make a distinction on edge sharpness. Naturally, none of the binoculars in this review are going to match the edge sharpness of a Swarovski or Leica. I gave the Pentax and the Minox the highest score with the other two being very close behind it.

The Vortex Viper is about half the price of the Bushnell Elite, making it a strong contender in the mid-priced binocular race. The higher priced Pentax DCF SP is one of my favorite binoculars and the Viper definitely gives it a run for its money. I chose the Minox BL/BR in this review as a standard lightweight 8x42 mid-priced roof prism binocular. Because the Vortex Viper isn't much more expensive than the Minox, I think it's a clear winner in its price class for the quality of glass and optical performance.

Update: Award Winning Vortex Viper!

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Weekend Update...

I made the short drive to Goose Pond Sanctuary this morning to see the Tundra Swans. Mark Martin stopped by and said his count was 680 swans. Scoping over the pond revealed a single Snow Goose, a probable Ross's Goose X Snow Goose hybrid, hundreds of Canada Geese, fewer Cackling Geese, many Mallards, Green-winged Teal and several Northern Pintail. Most of the swans were resting but some were forming small flocks and zooming around the perimeter of the pond - they're so beautiful in flight. Their gentle calls were very relaxing and it was good to be out.

Our backyard seems quiet at the feeders, but birds are definitely close by. Twice in the past few weeks I stood below one of the maple trees and pished continuously for a minute or so and watched what came out of the spruce trees. Today this brought out several Dark-eyed Juncos, 2 Red-breasted Nuthatches, 1 White-breasted Nuthatch, 1 White-throated Sparrow, 2 Black-capped Chickadees, a few House Finches and American Goldfinches, a Red-bellied Woodpecker and Downy Woodpecker. About the only birds that are conspicuous when watching the feeders from inside are Northern Cardinals and Blue Jays. There are also a few Hairy Woodpeckers that make regular rounds to suet. Perhaps this is unnecessary harassment (pishing), nevertheless it's interesting knowing the birds are around and not absent. They're just not making conspicuous trips to our feeders. Come snow cover, I'm sure that'll change.

On a personal note, I haven't been able to bird as much lately due to some recurring problems with my feet. I finally went to the doctor on Friday and was advised that my symptoms seem to indicate plantar fasciitis, which like most medical terms sounds worse than it actually is. It's been difficult for me to walk more than a mile or be on my feet for more than an hour at a time, so I'm off to a podiatrist in early January to find out more. For now, I'm keeping off my feet as much as reasonably possible. I'll try to keep blog posts relevant to whatever sort of birding or bird photography I'm up to, but there will probably be less in the short term. Putting a positive spin on being far more sedentary than I enjoy, I've been catching up on a lot of reading!

If you've been reading my blog for the past few years, I think it's pretty safe to assume you possess a keen interest and passion in all things related to birds. I recently picked up a copy of Laura Erickson's "101 Ways to Help Birds" and consider it to be one of the most valuable books about birds in my library. Reading her fine work, I found myself nodding in agreement, "Yeah, I do that. Yep...got that taken care of," etc. But I did discover and learn things I'm presently not doing that I could easily do, making the book purchase well worth its modest price. Ideas are knowledge that can be put into action or practice and her book is full of excellent ones. Laura's ideas and suggestions can save the lives of birds, so naturally I highly recommend her book!

Tundra Swan and White-breasted Nuthatch © 2006 Mike McDowell

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)